You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘General’ category.

A nice little question:

Given a regular pentagon with side length , what is the relationship between the area and the side-length?

First of all a pentagon:

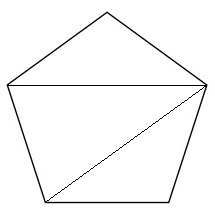

We use triangulation to cut it into a number of triangles:

With in each of the three triangles, there

in those angles around the edges, and, as there are five of them, they are each

.

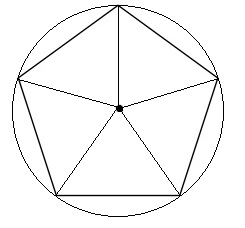

Next triangulate from the centre. With a plain oul pentagon we might not be sure that such a centre exists but if you start with a circle and inscribe five equidistant points along the circle, the centre of the circle serves as this centre:

As everything is symmetric, each of these triangles are the same and the ‘rays’ are also the same as they are all radii. The angle at the centre is equal to , and furthermore, by symmetry, the rays bisect the larger angles

and so each of these triangles are

.

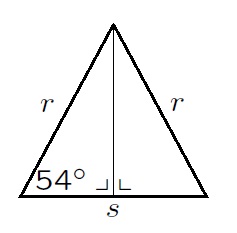

Using radians, because they are nicer, . Note that, where

is the perpendicular height:

.

A problem for another day is finding the exact value of . It is

Therefore the area of one such triangle is:

,

Therefore the area of the pentagon is five times this:

,

with . It might be possible to simply

further.

Quadratics are ubiquitous in mathematics. For the purposes of this piece a quadratic is a real-valued function of the form

,

where such that

. There is a little bit more to be said — particularly about the differences between a quadratic and a quadratic function but for those this piece is addressed to (third level: non-maths; all second level), the distinction is unimportant.

Geometry

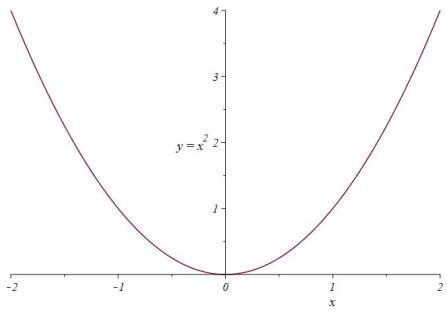

The basic object we study is the square function, ,

:

All quadratics look similar to . If

then the quadratic has this

geometry. Otherwise it looks like

and has

geometry

The geometry dictates that quadratics can have either zero, one or two real roots. A root of a function is an input such that

. As the graph of a function is of the form

, roots are such that

, that is where the graph cuts the

-axis. With the geometry of quadratics they can cut the

-axis no times, once (like

), or twice.

There are a number of ways of explaining why you cannot divide by zero. Here are my two favourites.

Any Set of Numbers Collapses to a Single Number

How old are you? Zero years old.

How tall are you? Zero metres old.

How many teeth do you have? Zero.

How many Superbowls has Tom Brady won? Zero

Yep, if you allow division by zero you only end up with one number to measure everything with.

After a long time I have finally completed my PhD studies when I handed in my hardbound thesis (a copy of which you can see here).

It was a very long road but thankfully now the pressure is lifted and I can enjoy my study of quantum groups and random walks thereon for many years to come.

As I said in the previous post, there is a duality:

Points on a Curve (Geometry) Solutions of an Equation (Algebra)

This means we can answer geometric questions using algebra and answer algebraic questions using geometry.

Problem

Consider the following two questions:

- Find the tangents to a circle

of a given slope.

- Find the tangents to a circle

through a given point.

Both can be answered using the duality principle.

Example

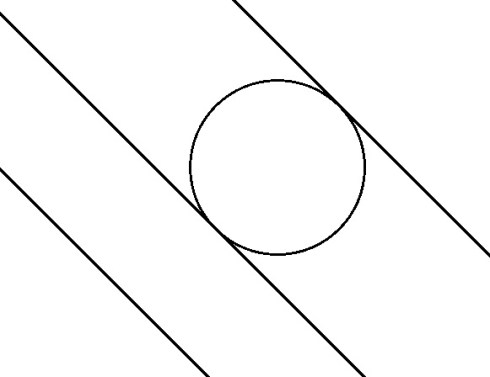

Find the tangents to the circle

that are

(a) parallel to the line

(b) through the point

[caution: the numbers here are disgusting]

Solution (a) i:

First of all a sketch (and the remark that a tangent is a line):

Here we see the circle and the line

on the bottom left. The two tangents we are looking for are as shown. They have the same slope as

and have only one intersection with

. These two pieces of information will allow us to find the equations of the tangents.

Arguably, the three central concepts in the theory of differential calculus are that of a function, that of a tangent and that of a limit. Here we introduce functions and tangents.

Functions

When looking at differential calculus, two good ways to think about functions are via algebraic geometry and interdependent variables. Neither give the proper, abstract, definition of a function, but both give a nice way of thinking about them.

Algebraic Geometry Approach

Let us set up the plane, . We choose a distinguished point called the origin and a distinguished direction which we call ‘positive

‘. Draw a line through the origin in the direction of positive

. This is the

-axis. Choose a unit distance for the

-direction.

Now, perpendicular to the -axis, draw a line through the origin. This is the

-axis. By convention positive

is anti-clockwise of positive

. Choose a unit distance for the

-direction.

This is the plane, :

Now points on the plane can be associated with a pair of numbers . For example, the point a distance one along the positive

and five along the negative

can be denoted by the coordinates (1,-5):

Similarly, I can take a pair of numbers, say (-1,3), and this corresponds to a point on the plane.

This gives a duality:

points on the plane pairs of numbers

Now consider the completely algebraic objects

.

This post follows on from this post where the logic for the below is discussed. I am not going to define here what easy means!

Here is the strategy/guiding principle:

Fundamental Principle of Solving ‘Easy’ Equations

Identify what is difficult or troublesome about the equation and get rid of it. As long as you do the same thing to both numbers (the “Lhs” and the “Rhs”), the equation will be replaced by a simpler equation with the same solution.

The following is taken (almost) directly from the first draft of my PhD thesis.

The Quantisation Functor

This functor can be used to motivate the correct notion of (the algebra of functions on) a quantum group. Note that the ‘quantised’ objects that are arrived at via this ‘categorical quantisation’ are nothing but the established definitions so this section should be considered as little more than a motivation. The author feels that introductory texts on quantum groups could include these ideas and that is why they are included here. This quantisation is the translation of statements about a finite group, into statements about the algebra of functions on

,

.

This notion of quantisation sits naturally in category theory where two functors — the functor and the dual functor — lead towards a satisfactory quantisation.

There is a right way to think about equations and there is a wrong way to think about equations. Let us not speak of the wrong way…

The equations I have in mind are those equations written in the form

,

where the aim is to find all the real numbers that ‘satisfy’ the equation.

We aren’t always taught the logic behind solving equations. The first thing to say is that many of us are trained to believe that this ‘‘ means the ‘the answer is’. This is not what equals means. This may have happened to us because while young children our textbooks had stuff like

written in them… the ‘answer’ of course being eight and the = sign almost suggests that we have to ‘do something’ to . Of course, this is not what equals means, and while the pupil who writes

is correct, the pupil who writes e.g.

,

has written a statement just as true as .

Introduction

In Ireland at least, we first encounter fractions at age 6-8. At this age, because of our maturity, while we might be capable of some conceptional understanding, by and large we are doing things by rote and, for example, multiplying fractions is just something that we do without ever questioning why fractions multiply together like that. This piece is aimed at second and third level students who want to understand why the ‘calculus’ of fractions is like it is.

Mathematicians can in a rigorous way, write down what a fraction is… this piece is pitched somewhere in between these constructions — perhaps seen in an undergraduate mathematics degree — and the presentation of fractions presented in primary school. It is closer in spirit to a rigorous approach but makes no claims at absolute rigour (indeed it will make no attempt at rigour in places). The facts are real number axioms.

Defining Fractions

We will define fractions in terms of integers and multiplication.

To get the integers we first define the natural numbers.

Definition 1: Natural Numbers

The set of natural numbers is the set of counting numbers

,

together with the operations of addition (+) and multiplication

.

Recent Comments