You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Grinds’ category.

Arguably, the three central concepts in the theory of differential calculus are that of a function, that of a tangent and that of a limit. Here we introduce functions and tangents.

Functions

When looking at differential calculus, two good ways to think about functions are via algebraic geometry and interdependent variables. Neither give the proper, abstract, definition of a function, but both give a nice way of thinking about them.

Algebraic Geometry Approach

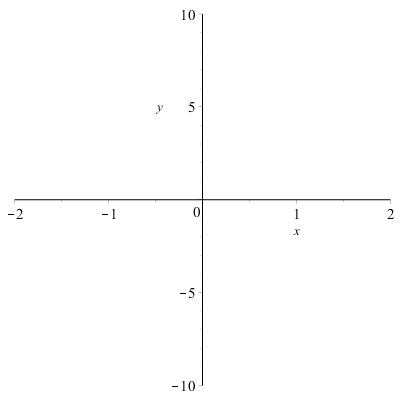

Let us set up the plane, . We choose a distinguished point called the origin and a distinguished direction which we call ‘positive

‘. Draw a line through the origin in the direction of positive

. This is the

-axis. Choose a unit distance for the

-direction.

Now, perpendicular to the -axis, draw a line through the origin. This is the

-axis. By convention positive

is anti-clockwise of positive

. Choose a unit distance for the

-direction.

This is the plane, :

Now points on the plane can be associated with a pair of numbers . For example, the point a distance one along the positive

and five along the negative

can be denoted by the coordinates (1,-5):

Similarly, I can take a pair of numbers, say (-1,3), and this corresponds to a point on the plane.

This gives a duality:

points on the plane pairs of numbers

Now consider the completely algebraic objects

.

This post follows on from this post where the logic for the below is discussed. I am not going to define here what easy means!

Here is the strategy/guiding principle:

Fundamental Principle of Solving ‘Easy’ Equations

Identify what is difficult or troublesome about the equation and get rid of it. As long as you do the same thing to both numbers (the “Lhs” and the “Rhs”), the equation will be replaced by a simpler equation with the same solution.

There is a right way to think about equations and there is a wrong way to think about equations. Let us not speak of the wrong way…

The equations I have in mind are those equations written in the form

,

where the aim is to find all the real numbers that ‘satisfy’ the equation.

We aren’t always taught the logic behind solving equations. The first thing to say is that many of us are trained to believe that this ‘‘ means the ‘the answer is’. This is not what equals means. This may have happened to us because while young children our textbooks had stuff like

written in them… the ‘answer’ of course being eight and the = sign almost suggests that we have to ‘do something’ to . Of course, this is not what equals means, and while the pupil who writes

is correct, the pupil who writes e.g.

,

has written a statement just as true as .

Introduction

In Ireland at least, we first encounter fractions at age 6-8. At this age, because of our maturity, while we might be capable of some conceptional understanding, by and large we are doing things by rote and, for example, multiplying fractions is just something that we do without ever questioning why fractions multiply together like that. This piece is aimed at second and third level students who want to understand why the ‘calculus’ of fractions is like it is.

Mathematicians can in a rigorous way, write down what a fraction is… this piece is pitched somewhere in between these constructions — perhaps seen in an undergraduate mathematics degree — and the presentation of fractions presented in primary school. It is closer in spirit to a rigorous approach but makes no claims at absolute rigour (indeed it will make no attempt at rigour in places). The facts are real number axioms.

Defining Fractions

We will define fractions in terms of integers and multiplication.

To get the integers we first define the natural numbers.

Definition 1: Natural Numbers

The set of natural numbers is the set of counting numbers

,

together with the operations of addition (+) and multiplication

.

Consider the following question. is supposed to represent the sale price of a hotel room, while

represents the cost price. Therefore the profit is given by

. I am going to use the term expected average as opposed to the more standard expected value or expectation.

There is a problem with the interpretation and I wouldn’t treat this particular exercise with much importance.

Suppose that and

are independent random variables with distributions

Find the expected average of the profit on a single room. Find the expected average of the profit on 1,000 rooms. Find the probability that the profit on 1,000 rooms is less than 20,000.

Solution : The expected average of a variable is given by:

.

Now expected average is linear:

.

Introduction

This is just a short note to provide an alternative way of proving and using De Moivre’s Theorem. It is inspired by the fact that the geometric multiplication of complex numbers appeared on the Leaving Cert Project Maths paper (even though it isn’t on the syllabus — lol). It assumes familiarity with the basic properties of the complex numbers.

Complex Numbers

Arguably, the complex numbers arose as a way to find the roots of all polynomial functions. A polynomial function is a function that is a sum of powers of . For example,

is a polynomial. The highest non-zero power of a polynomial is called it’s degree. Ordinarily at LC level we consider polynomials where the multiples of

— the coefficients — are real numbers, but a lot of the theory holds when the coefficients are complex numbers (note that the Conjugate Root Theorem only holds when the coefficients are real). Here we won’t say anything about the coefficients and just call them numbers.

Definition

Let be numbers such that

. Then

,

is a polynomial of degree .

In many instances, the first thing we want to know about a polynomial is what are its roots. The roots of a polynomial are the inputs such that the output

.

Theorem: Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality

Let and

be sequences of real numbers. Then we have

.

Proof : Consider the following quadratic function :

.

Note at this point that for all

.

.

That is is a

or `

‘ positive quadratic so has one or no roots. That means the roots are real and repeated or complex so that we have

where

:

Now take square roots (remembering .)

With the new Project Maths programme being developed as we speak, diligent students might like to know which proofs are examinable under the new syllabus so they know which to look at.

It can be difficult to sift through the syllabi at projectmaths.ie but I have gone through them and here are the proofs required.

This is a short note covering pensions as done in LC HL Project Maths. I do not know how pensions are calculated “in the real world”.

Fixed Number of Payouts

Suppose you want a pension that will pay you €20,000 per year for 25 years after retirement. How much should you have in your pension fund on retirement in order to have this? Suppose further that money can be invested at 3% per annum.

Method 1

Suppose we need the pension fund to contain €X on retirement. Let be the amount of money in the pension fund after

years and suppose the pension fund is invested at 3%. Well, in the first year we need:

,

but then take out €20,000:

We then accrue interest on this (capital + interest = ) — but then withdraw €20,000 at the end of the first year so:

.

Now this accrues interest but €20,000 is withdrawn:

.

Taken from here.

A manufacturing company keeps records of the numbers of defective items it produces per day. A random sample of days was selected. From their records, the company calculated the proportion of defective items produced per day. The frequency distribution of of proportions defective is as follows:

|

Proportion Defective |

Number of Days |

|

0 – 1% |

66 |

|

1 – 2% |

44 |

|

2 – 3% |

32 |

|

3 – 4% |

19 |

|

4 – 5% |

8 |

|

5 – 6% |

5 |

|

6 – 8% |

4 |

|

8% or more |

2 |

(a)

Draw a histogram for the distribution on proportions defective. Comment on its shape.

The histogram is skewed to the left towards 0.

(b)

Explain how you determined the heights of the bars for the last two frequency classes in preparing the histogram.

A histogram is constructed such that the area under each bar is equal to the number in the class interval. For the 6 – 8% class interval the base was 2 and the number in the class interval was 4 so we wanted height base = 2; i.e. the base to equal 2. In the 8 – 100% the height is effectively zero — by the same analysis we have height =

.

(c)

Provide a numerical measure to describe the proportions defective. Justify your choice of numerical measure.

Using the formula for the mean, , of a frequency distribution:

,

where the sum is over all class intervals where is the number of elements in the

th class interval and

is the value of the midpoint of the

th class interval.

We will however crop the 8 – 100% class to 8 – 10% to prevent a massive bias here. This will improve our calculation because any data above 10% is clearly an outlier (which is bad for the mean — see below).

Thus we get

.

We use the mean as there are not too many outliers and while the data is skewed, the data is relatively spread out.

(d)

Calculate the first quartile and interpret it’s value. State any assumptions you make. Assess whether these assumptions are valid.

There are 180 days in total so one quarter is 45. Now the lowest 45 are in the class interval 0 – 1% which actually includes 66 elements. Hence we look to take just of the first bar. We do this as follows:

So the first quarter lies between 0 and 0.682%… therefore the first quartile is 0 — 0.682%. The interpretation is that the 25% best days have less than 0.682% defections.

To do this we assume that the distribution is uniform across the class interval 0 – 1%.

While this answer may well be accurate we can’t be too sure — particularly when the model suggest there are days with very little defections. For example, this assumption demands that there is a day when there are 0.015% defections; i.e. 1 in 6,666 — but does the manufacturer ever make this many a day?

(e)

The manufacturing company operates a policy which specifies that if the proportion defective exceeds 4.75% on any given day, an investigation of the manufacturing process must be undertaken. Estimate the percentage of days on which such an investigation would be undertaken.

Looking at the histogram there were 5+4+2=11 days when the proportion defective exceeded 5%. Now the 4.75 – 5% class sub-interval corresponds to 1/4 of the 4 – 5% class interval — that is 2 days. Hence we have 11+2=13/180 days when the proportion defective exceeded 4.75%. 13/180 translates to an estimation of 7.2% of days of proportions defective exceeding 4.75%.

(f)

The manufacturing company reviewed the policy referred to in part (e). They want to change the cut-off for the proportion defective that necessitates the investigation of the manufacturing process (currently 4.75%). Estimate the cut-off that should be used to ensure that the percentage of days on which the investigations would be undertaken is at most 5%.

We want to adjust the 7.2% above to 5%. 5% of 180 days is nine days. So which were the nine worst days? We have six days worse than 6% and then we want to take 3 of the five bad days in 5 -6% class interval to make up the worst nine days. Now we want to take, therefore, the class sub-interval 5.4 – 6%, which is 3/5 of that interval. Hence the new threshold is 5.4% (which estimates an investigation on 5% of days).

Recent Comments