You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Probability Theory’ category.

Consider the symmetric group . Let

count the number of fixed points of a permutation

. Where

, we have that for a random permutation

chosen with respect to the uniform distribution, the

converges in distribution to

in the sense that:

.

In this note we will look at the distribution in the case where the uniform distribution is conditioned on .

Theorem

Let be chosen according to the distribution uniform on permutations for which one is a fixed point. The number of fixed points has distribution

in the sense that, where

,

.

Proof: What can be shown, ostensibly from stuff from the quantum permutation side of the house is that, where is integration against the uniform distribution, and

is integration against the uniform distribution on permutations with one a fixed point, that, for

:

,

the -st Bell number. Now consider the moments of

:

,

using the fact that the Bell numbers are the moments of that Poisson distribution and the standard recurrence for the Bell numbers.

Local vs Global Conditioning of Quantum Permutations

In the quantum case we define

,

where is the fundamental magic representation. The moments of

with respect to the Haar state are the Catalan numbers and it follows that the law of

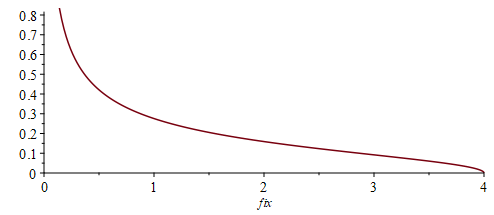

is a Marchenko-Pastur distribution, with density

:

Note that when we measure the Haar state with some finite spectrum version of we find:

- the probability of finding an integer number of fixed points is zero, and

- independently of

, the probability of finding more than four fixed points is zero.

In the classical case above when we chose the permutation uniformly from those who fix one, there are two ways of viewing it:

- we pick an element of

that fixes one, OR

- we consider the isotropy subgroup

and choose our permutation from

.

Classically, these are the same thing. In the quantum case these two things can be interpreted differently. The second case is quite clear in the quantum case. For , we take the isotropy

via the quotient

.

The analogue of the uniform distribution on here is the Haar idempotent

. Note this maps

to

. Now, using the fact that

, the Catalan number, we have that the moments of

with respect to

is the binomial transform of the Catalan numbers (the binomial transform of

is

). It follows, using similar stuff to the above, that the distribution of

with respect to

is just a shifted version of Marchenko–Pastur:

I guess this is marginally more interesting than the unshifted version.

Now, what about an analogue of “we pick an element of that fixes one”. So if we take the Haar state and measure the observable

that asks of a quantum permutation, does it fix one, we get, conditioned on this, the state:

.

And, it turns out, as above, using stuff from the quantum permutation side of the house:

.

Quite quickly from here we find that the density of the distribution of with respect to

is

This is so interesting:

- it doesn’t change the support — we still find between 0 and 4 fixed points,

- we have a new symmetry about

, we had another unexpected symmetry here.

- the mean jumps from one to two, that is not unexpected, but

- the mode jumps from zero to two!

- even though we have observed one to one, there can still be less than one fixed point when we measure… and this happens with probability

.

The next obvious question is what happens with:

Epilogue?

So what about this local vs global conditioning? Well, no matter what subsequent measurements are made to , we will always find that one is a fixed point. That conditioning is ‘global’.

This is not the case with , and why the support of the law is not bounded above one, like that of the globally conditioned

. In fact, there is a non-zero probability that

is observed to fix two but then subsequently not fix one anymore. That conditioning was only local: the probability that

fixes one is 100%… but subsequent measurements can destroy that conditioning… it is only local.

Classical Warm-up

Let be the classical permutation group on

symbols. The algebra of continuous functions

on

is generated by indicator functions:

.

This algebra is commutative, but we will use some non-commutative algebraic analogues. Let be the uniform probability distribution on

and by

the associated state on

:

When choosing a permutation at random what is the probability that it sends ? Well, this will equal, in some notation we won’t fully explain here:

.

Once this has been observed, there is a conditioning of the state :

.

The state was given by but is now given by

. Now, after having observed this random permutation mapping

, we can ask it another question.

Consider a subset and define:

.

This is an observable, which basically asks of a permutation, do you map three into ? One for yes, zero for no. So let us ask this of

:

What is the probability that a random permutation maps three into

after having been observed mapping one to one?

We find, with a fairly elementary calculation that the answer to this question is:

.

If , we get further conditioning, to let us say

:

What is the probability that after seeing after

we see

? We find it is:

.

Therefore, where means after, and the state-conditioning implicit

Now let us ask a ridiculous question. What was the probability that ? But

is just a conditioning of

, which mapped one to one with probability one:

.

Of course the answer is zero. Can we actually see it in the above framework: well, yes, because the algebra of functions is commutative. You end up with evaluating a state at

,

but commutativity sees … and no permutation maps one to one and one to two (you’d need a relation to do that), and so

, so is the length five monomial above, and so is the probability we spoke about.

We don’t have to do state conditioning and multiplication to calculate the probability that a random permutation maps one to one, then maps three into , then maps two to two though. Where

:

.

Let us remark that this probability is increasing in : the less we specify about the event, in this case represented by the projection

, the more general it is, the larger the probability.

Let’s Go Quantum

In the case of quantum permutations, so talking the ridiculous question of asking what is the probability that a quantum permutation maps one to two after it had previously mapped one to one… is no longer zero. Where

, the probability of the analogue of a “random” quantum permutation, the Haar state

doing this is:

Anyway, the quantum versions of the are entries

of a universal magic unitary. We say:

,

where . We find this probability is:

.

This is also increasing in . Again, the less specificity about the event, the greater the probability.

This quantity is related to the classical probability above, and there are asymptotic similarities. Writing , where

is the complement of

in

:

I guess this also says, the larger , the more similar the classical and quantum probabilities.

A twist

What if instead of looking at after

after

but instead we asked about

? This should be non-zero, but what is the dependence on

?

From our classical intuition, we would probably just expect, well, the same really. The larger the value of , the less we are saying about the event. The larger the probability. But in fact this is not the case. The probability is largest when

is close to

. We will write down the probability, and then explain, mathematically, why the symmetry with respect to

, with respect to

:

.

Proof: Consider . Insert between them

:

.

Like in the classical case, by definition here, . So split into two sums:

.

Now, classically, this is just a sum of zero terms equal to zero, but not in the quantum world where we have these . They are not positive though. We can now split:

.

Now take the of both sides to show that:

This yields the strange probability above. I think any intuition I have for this would be very much post-hoc. I think I will just let it hang there as something weird, cool and mysterious about quantum permutations…

Alice, Bob and Carol are hanging around, messing with playing cards.

Alice and Bob each have a new deck of cards, and Alice, Bob, and Carol all know what order the decks are in.

Carol has to go away for a few hours.

Alice starts shuffling the deck of cards with the following weird shuffle: she selects two (different) cards at random, and swaps them. She does this for hours, doing it hundreds and hundreds of times.

Bob does the same with his deck.

Carol comes back and asked “have you mixed up those decks yet?” A deck of cards is “mixed up” if each possible order is approximately equally likely:

She asks Alice how many times she shuffled the deck. Alice says she doesn’t know, but it was hundreds, nay thousands of times. Carol says, great, your deck is mixed up!

Bob pipes up and says “I don’t know how many times I shuffled either. But I am fairly sure it was over a thousand”. Carol was just about to say, great job mixing up the deck, when Bob interjects “I do know that I did an even number of shuffles though.“.

Why does this mean that Bob’s deck isn’t mixed up?

Abstract

Necessary and sufficient conditions for a Markov chain to be ergodic are that the chain is irreducible and aperiodic. This result is manifest in the case of random walks on finite groups by a statement about the support of the driving probability: a random walk on a finite group is ergodic if and only if the support is not concentrated on a proper subgroup, nor on a coset of a proper normal subgroup. The study of random walks on finite groups extends naturally to the study of random walks on finite quantum groups, where a state on the algebra of functions plays the role of the driving probability. Necessary and sufficient conditions for ergodicity of a random walk on a finite quantum group are given on the support projection of the driving state.

Link to journal here.

In my pursuit of an Ergodic Theorem for Random Walks on (probably finite) Quantum Groups, I have been looking at analogues of Irreducible and Periodic. I have, more or less, got a handle on irreducibility, but I am better at periodicity than aperiodicity.

The question of how to generalise these notions from the (finite) classical to noncommutative world has already been considered in a paper (whose title is the title of this post) of Fagnola and Pellicer. I can use their definition of periodic, and show that the definition of irreducible that I use is equivalent. This post is based largely on that paper.

Introduction

Consider a random walk on a finite group driven by

. The state of the random walk after

steps is given by

, defined inductively (on the algebra of functions level) by the associative

.

The convolution is also implemented by right multiplication by the stochastic operator:

,

where has entries, with respect to a basis

. Furthermore, therefore

,

and so the stochastic operator describes the random walk just as well as the driving probabilty

.

The random walk driven by is said to be irreducible if for all

, there exists

such that (if

)

.

The period of the random walk is defined by:

.

The random walk is said to be aperiodic if the period of the random walk is one.

These statements have counterparts on the set level.

If is not irreducible, there exists a proper subset of

, say

, such that the set of functions supported on

are

-invariant. It turns out that

is a proper subgroup of

.

Moreover, when is irreducible, the period is the greatest common divisor of all the natural numbers

such that there exists a partition

of

such that the subalgebras

of functions supported in

satisfy:

and

(slight typo in the paper here).

In fact, in this case it is necessarily the case that is concentrated on a coset of a proper normal subgroup

, say

. Then

.

Suppose that is supported on

. We want to show that for

. Recall that

.

This shows how the stochastic operator reduces the index .

A central component of Fagnola and Pellicer’s paper are results about how the decomposition of a stochastic operator:

,

specifically the maps can speak to the irreducibility and periodicity of the random walk given by

. I am not convinced that I need these results (even though I show how they are applicable).

Stochastic Operators and Operator Algebras

Let be a

-algebra (so that

is in general a virtual object). A

-subalgebra

is hereditary if whenever

and

, and

, then

.

It can be shown that if is a hereditary subalgebra of

that there exists a projection

such that:

.

All hereditary subalgebras are of this form.

In a recent preprint, Haonan Zhang shows that if (where

is a Sekine Finite Quantum Group), then the convolution powers,

, converges if

.

The algebra of functions is a multimatrix algebra:

.

As it happens, where , the counit on

is given by

, that is

, dual to

.

To help with intuition, making the incorrect assumption that is a classical group (so that

is commutative — it’s not), because

, the statement

, implies that for a real coefficient

,

,

as for classical groups .

That is the condition is a quantum analogue of

.

Consider a random walk on a classical (the algebra of functions on is commutative) finite group

driven by a

.

The following is a very non-algebra-of-functions-y proof that implies that the convolution powers of

converge.

Proof: Let be the smallest subgroup of

on which

is supported:

.

We claim that the random walk on driven by

is ergordic (see Theorem 1.3.2).

The driving probability is not supported on any proper subgroup of

, by the definition of

.

If is supported on a coset of proper normal subgroup

, say

, then because

, this coset must be

, but this also contradicts the definition of

.

Therefore, converges to the uniform distribution on

Apart from the big reason — that this proof talks about points galore — this kind of proof is not available in the quantum case because there exist that converge, but not to the Haar state on any quantum subgroup. A quick look at the paper of Zhang shows that some such states have the quantum analogue of

.

So we have some questions:

- Is there a proof of the classical result (above) in the language of the algebra of functions on

, that necessarily bypasses talk of points and of subgroups?

- And can this proof be adapted to the quantum case?

- Is the claim perhaps true for all finite quantum groups but not all compact quantum groups?

Quantum Subgroups

Let be a the algebra of functions on a finite or perhaps compact quantum group (with comultiplication

) and

a state on

. We say that a quantum group

with algebra of function

(with comultiplication

) is a quantum subgroup of

if there exists a surjective unital *-homomorphism

such that:

.

The Classical Case

In the classical case, where the algebras of functions on and

are commutative,

There is a natural embedding, in the classical case, if is open (always true for

finite) (thanks UwF) of

,

,

with for

, and

otherwise.

Furthermore, is has the property that

,

which resembles .

In the case where is a probability on a classical group

, supported on a subgroup

, it is very easy to see that convolutions

remain supported on

. Indeed,

is the distribution of the random variable

,

where the i.i.d. . Clearly

and so

is supported on

.

We can also prove this using the language of the commutative algebra of functions on ,

. The state

being supported on

implies that

.

Consider now two probabilities on but supported on

, say

. As they are supported on

we have

and

.

Consider

,

that is is also supported on

and inductively

.

Some Questions

Back to quantum groups with non-commutative algebras of functions.

- Can we embed

in

with a map

and do we have

, giving the projection-like quality to

?

- Is

a suitable definition for

being supported on the subgroup

.

If this is the case, the above proof carries through to the quantum case.

- If there is no such embedding, what is the appropriate definition of a

being supported on a quantum subgroup

?

- If

does not have the property of

, in this or another definition, is it still true that

being supported on

implies that

is too?

Edit

UwF has recommended that I look at this paper to improve my understanding of the concepts involved.

Slides of a talk given at the Irish Mathematical Society 2018 Meeting at University College Dublin, August 2018.

Abstract Four generalisations are used to illustrate the topic. The generalisation from finite “classical” groups to finite quantum groups is motivated using the language of functors (“classical” in this context meaning that the algebra of functions on the group is commutative). The generalisation from random walks on finite “classical” groups to random walks on finite quantum groups is given, as is the generalisation of total variation distance to the quantum case. Finally, a central tool in the study of random walks on finite “classical” groups is the Upper Bound Lemma of Diaconis & Shahshahani, and a generalisation of this machinery is used to find convergence rates of random walks on finite quantum groups.

Distances between Probability Measures

Let be a finite quantum group and

be the set of states on the

-algebra

.

The algebra has an invariant state

, the dual space of

.

Define a (bijective) map , by

,

for .

Then, where and

, define the total variation distance between states

by

.

(Quantum Total Variation Distance (QTVD))

Standard non-commutative machinary shows that:

.

(supremum presentation)

In the classical case, using the test function , where

, we have the probabilists’ preferred definition of total variation distance:

.

In the classical case the set of indicator functions on the subsets of the group exhaust the set of projections in , and therefore the classical total variation distance is equal to:

.

(Projection Distance)

In all cases the quantum total variation distance and the supremum presentation are equal. In the classical case they are equal also to the projection distance. Therefore, in the classical case, we are free to define the total variation distance by the projection distance.

Quantum Projection Distance  Quantum Variation Distance?

Quantum Variation Distance?

Perhaps, however, on truly quantum finite groups the projection distance could differ from the QTVD. In particular, a pair of states on a factor of

might be different in QTVD vs in projection distance (this cannot occur in the classical case as all the factors are one dimensional).

Slides of a talk given at the Topological Quantum Groups and Harmonic Analysis workshop at Seoul National University, May 2017.

Abstract A central tool in the study of ergodic random walks on finite groups is the Upper Bound Lemma of Diaconis & Shahshahani. The Upper Bound Lemma uses the representation theory of the group to generate upper bounds for the distance to random and thus can be used to determine convergence rates for ergodic walks. These ideas are generalised to the case of finite quantum groups.

Recent Comments